“Experiencing the changes in life over the years has meant more to me than simple aging. It has meant watching the landscape and the world become more tame, drab, and developed. Human life and wildlife are both losing their world.” – Barbara Kerr

I have spent more than a few hours in January reviewing Ken Burns’ recent documentary The National Parks: America’s Best Idea and have learned a great deal from it, both factually and emotionally. The documentary has helped me to piece together some scattered thoughts.

A map was drawn up by the National Park Service of Petit Jean.

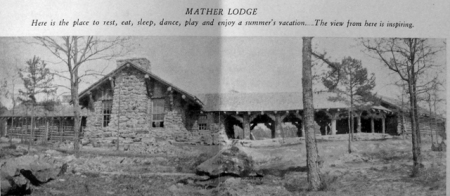

I found it interesting, even before I ever served as a park interpreter at Petit Jean, that this state park has ties, and some similarities, to national parks: We have a lodge named for the first Park Service Director, Stephen Mather, who visited here in the 1920s to help strengthen a new Conference of State Parks. Our country doctor/park founder, T.W. Hardison, originally had the national park idea in mind when he first met with Mather. They would meet again, and Hardison would come to know Mather as a friend and fellow conservationist. Petit Jean State Park has a set of archived park plans (on display at the visitor center) drawn up by the National Park Service during the time of the Civilian Conservation Corps – another tie. The idea of setting this beautiful, rugged area aside to be conserved for future generations parallels the notion that began the national parks. It follows the same pattern. As our Executive Director of Arkansas Parks and Tourism, Richard Davies, noted in a talk back in December, “Our state parks are the ‘child’ of national parks.” It’s a pretty accurate metaphor.

Though I believed I knew the answer, I have asked myself on several occasions recently, “Why do I like parks so much?” And the more I think about it, the deeper the answers run. There are volumes.

One reason might be summed up by the title of a Thomas Wolfe novel, You Can’t Go Home Again. Wolfe’s title refers to change. In time, change may alter any place – even home, or maybe especially home – to a point that it is no longer the same place. It’s not home as you knew it anymore. You can’t go there anymore. The sentence/title strikes a chord with me because it is so true. But parks are, by nature, change-resistant. The idea is to let them remain “home” to the people who visit them generation after generation. A person who made the hike to Cedar Falls fifty years ago can return today, make the hike, and little has changed. Somewhere, deep down, that must be a source of inspiration and perhaps a source of great relief as well.

Hiking the trails at Petit Jean State Park is timeless.

When I was eight years old, a clever second-grader, I made one of my first organized hikes – a very special one. It was not in a park, but it was in a place very much like a park – a natural area with an expansive reach and an interesting history. Four generations of my family had just come back from a service at a small country church. My grandmother provided music at the church’s piano. There were my younger sister and myself, our parents, my father’s parents, and my father’s mother’s parents. From my great-grandparents’ old country house, we all made an afternoon walk up our home stream, the North Fork of Ozan Creek. This old creek sliced through the Gulf Coastal Plain of southwest Arkansas, revealing colorful rounded stones washed away from conglomerate outcrops and mounds of slate-blue clay the local people called “Indian soap.” The creek’s water was clear and churned down riffles into long pools that again became lively riffles. Caddo burial mounds dotted the countryside along the creek, and artifacts from that culture turned up everywhere.

We hiked for several miles that afternoon, on a pretty well-established trail, and for the first time I got to see places that would become an embedded part of my early life. There was one spring, in particular, that flowed down a clay embankment, leaving multi-hued mineral patterns on a cusp that faced a small pool which emptied into the creek. My buddies and I would later dub it “Buffalo Spring” because of its brown colors. The trail builders, whoever they may have been, created bench paths that cut midway along the sides of the bluffs some thirty feet up over the creek. Hardwood and pine canopied the creek corridor, and down along the creek bed were springs and more springs, feeder streams, canebrakes, and openings into fields. Our final destination that day was a waterfall, about five feet high and twenty feet across, with a darn good swimming hole washed out beneath it. And I found my eight-year-old self in love with a place.

Late that afternoon, I settled in warm by the fireplace at my great-grandparents’ house, thinking about it all. I hoped that we would all do the hike again next week. But it didn’t happen. Then I wished that we would do the hike together again later on. But time passed, and changes came. My great-grandparents and grandparents grew older, my parents grew busier, and that group of eight would never make the hike to the waterfall again. For the four generations, it turned out to be a one-time experience. Later in my childhood, though, I became as intimately familiar with the Ozan and its surroundings as I was with each of those members of my own family. Three other boy companions lived just down the road. We kept the Ozan Creek company for years and, looking back, were pretty good caretakers.

We witnessed the dynamics of the stream, knew the scents and sounds and responses to seasons. Spring rains brought the big, swift, brown water out of the banks. When the creek settled down, expansive new rock bars appeared, newly washed out swimming holes were discovered, while other pools were filled in with stone and gravel. One swimming hole, the flood-scoured floor newly-cleared to reveal a large deposit of blue clay, became known to local people as the “Blue Hole” or “Clay Bottom.” I was baptized in that swimming hole one summer Sunday afternoon. Afterwards, my buddies threw me off the diving bank and “re-baptized” me. Summer droughts brought shallow pools laced with algae; riffles turned to dry rock. Long-ear sunfish made nests in shallows and dutifully defended them. Small chain pickerel darted beneath grassy banks. There were cottonmouths all along the creek, a species that I would later learn defines a healthy watershed – but if you want to stay healthy, don’t let them get their fangs into you.

As we grew older, our territory expanded. A few miles downstream, the Ozan ran into a wetland. There was a beaver dam the length of a football field, and we learned of old natural caves that had been slowly eroded into the sandstone hills not far from the beaver pond. Waterfowl flew in by hundreds. One year, on my best friend’s birthday, we were set free to hike across the bottoms. His mother picked us up at a pre-determined spot late that afternoon. It was an unforgettable day.

By the time I was a senior in high school, “progress” was afoot, and there were plans for the North Fork of Ozan Creek. Change was on its way. The USDA Soil Conservation Service was in the final stages of building “watershed dams” on many of the streams that flowed into the rich farmland miles downstream – this theoretically to control flooding and to save crops. I vividly remember hiking upstream one spring day and being wide-eyed to find dozers and earth movers beginning the process of building a huge earthen dam across the Ozan – a quarter-mile of dirt, dust and noise. Once the dam was completed, the entirety of water in the creek was funneled down a chamber and fed through a pipe about three and one-half feet in diameter. Only the heated top-water of the new reservoir made it to the other side of the dam. On a summer day, the water that fed from the dam into the old creek bed was as warm as bathwater to the touch. And, as several years passed, the living, changing creek that I had known for so long all but vanished. Only a withered remnant remained, slowly filling with soil and fallen trees. The Ozan had become a mere, winding overgrown ditch.

A wealthy rancher from the west bought the wetland area. Before long there were more dozers and chainsaws busy clearing and draining the bottomland. A new channel was cut for the stream to run through, a straight drainage ditch. Being paranoid that someone would become injured or trapped in one of the old sandstone caverns, the landowner even had the bull dozers cave in and seal off the entrances. In time, and to the amazement of some of the local residents, the wetland became a cow pasture.

Later still, when I was in my mid-twenties, I made a scouting walk up the Ozan. I had a new son and had it in mind to make some of my childhood treks with him once he became old enough. By then, a new housing development was beginning to spring up in the fields above the bluffs. There were brand new, large homes being built for the upwardly mobile of the nearest town. Once I came upon Buffalo Spring, I was dismayed to find, in the pool beneath the cusp, a large wooden cable spool, dumped along with lesser bits and pieces of leftover construction material. Developers and new residents were using the creek as a garbage dump. Further on, I found barbed wire strung all the way to the creek banks. The old walking trail was gone. The bench paths along the bluffs were eroded away. As more time went by, the wealthy occupants of the Ozan estates began to use the creek for riding popular, new all-terrain-vehicles, scarring the creek bed and its banks with deep, muddy ruts as well as leaving litter. It was a whole new change and not necessarily for the better.

Scenarios similar to mine have happened in many places during the past several decades. I hear it from like-minded people all over the world: “I once knew this lovely place. It’s changed now.”

Why do I like parks so much? One reason is I can’t go home again. Only in distant memory can I walk along the path that my family’s four generations took one Sunday afternoon long ago. As I grow older, I look on and see, in real terms, what happens if an inspiring, natural place is not protected in some way. There is certainty that it will be degraded or vanish entirely, especially with new populations, changing values, and a drive, by some, to turn natural resources into more wealth.

One of the most comforting thoughts that I can imagine is that when my granddaughter is grown and tall, and a force to be reckoned with, that there will still be a Boy Scout Trail at Petit Jean State Park. I hope that she will be out on it with a daypack strapped to her back, testing strong legs against stone, sunrays still heating up the walls of the ancient slot canyons in the Seven Hollows. And I hope I’m there, trying to keep up. Parks such as Petit Jean, for us and even for those who exist out in the distant future, give special places and the people who know them a chance to endure.

“The legacy of Arkansas State Parks is to preserve our state’s diverse beauty and history, so that all Arkansans and visitors may find emotional and intellectual connections to their heritage.”

BT Jones, Park Interpreter

BT Jones is a park interpreter at Petit Jean State Park and has worked there since 2005. He holds a master’s degree in education from the University of Arkansas at Little Rock. BT is a member of the National Association for Interpretation (NAI) and holds a Certified Interpretive Guide credential. He is also a Leave No Trace (LNT) master educator and works as an advocate for Arkansas wilderness. BT’s pasttimes are nature and wildlife photography, hiking and backpacking, and helping to preserve Arkansas’s wilderness and natural areas. He most enjoys hiking with park visitors and presenting programs on Petit Jean’s natural and historical features.

Posted by Arkansas State Parks

Posted by Arkansas State Parks

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter YouTube

YouTube